Greece

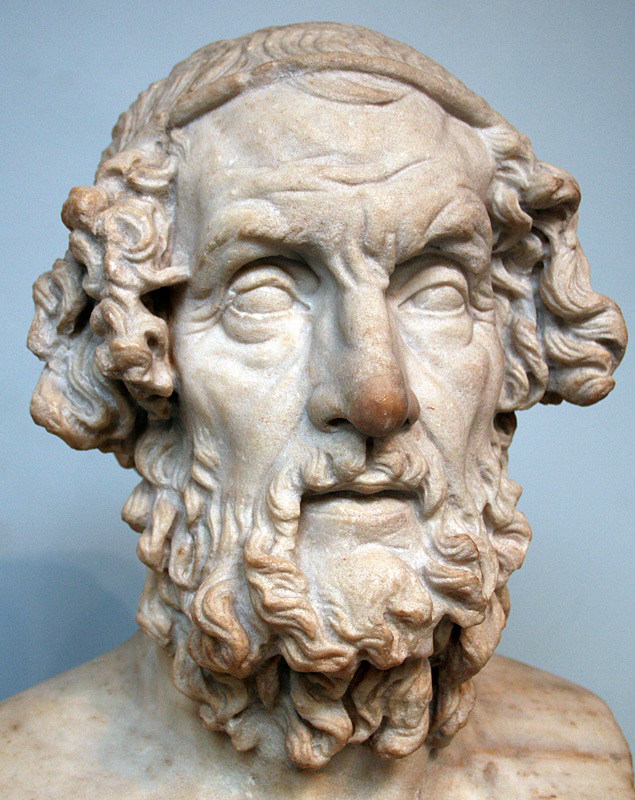

Ancient Greek society placed considerable emphasis on literature and, according to many, the whole Western literary tradition began there, with the epic poems of Homer.

In addition to the invention of the epic and lyric forms of poetry, though, the Greeks were also essentially responsible for the invention of drama, and they produced masterpieces of both tragedy and comedy that are still reckoned among the crowning achievements of drama to this day.

Indeed, there is scarcely an idea discussed today that has not already been debated and embroidered on by the writers of ancient Greece.

The epic poems attributed to Homer are usually considered the first extant work of Western literature, and they remain giants in the literary canon for their skillful and vivid depictions of war and peace, honor and disgrace, love and hatred.

Hesiod was another very early Greek poet and his didactic poems give us a systematic account of Greek mythology, the creation myths and the gods, as well as an insight into the day-to-day lives of Greek farmers of the time.

The fables of Aesop represent a separate genre of literature, unrelated to any other, and probably developed out of an oral tradition going back many centuries.

Sappho and, later, Pindar, represent, in their different ways, the apotheosis of Greek lyric poetry.

The earliest known Greek dramatist was Thespis, the winner of the first theatrical contest held at Athens in the 6th Century BCE. Choerilus, Pratinas and Phrynichus were also early Greek tragedians, each credited with different innovations in the field.

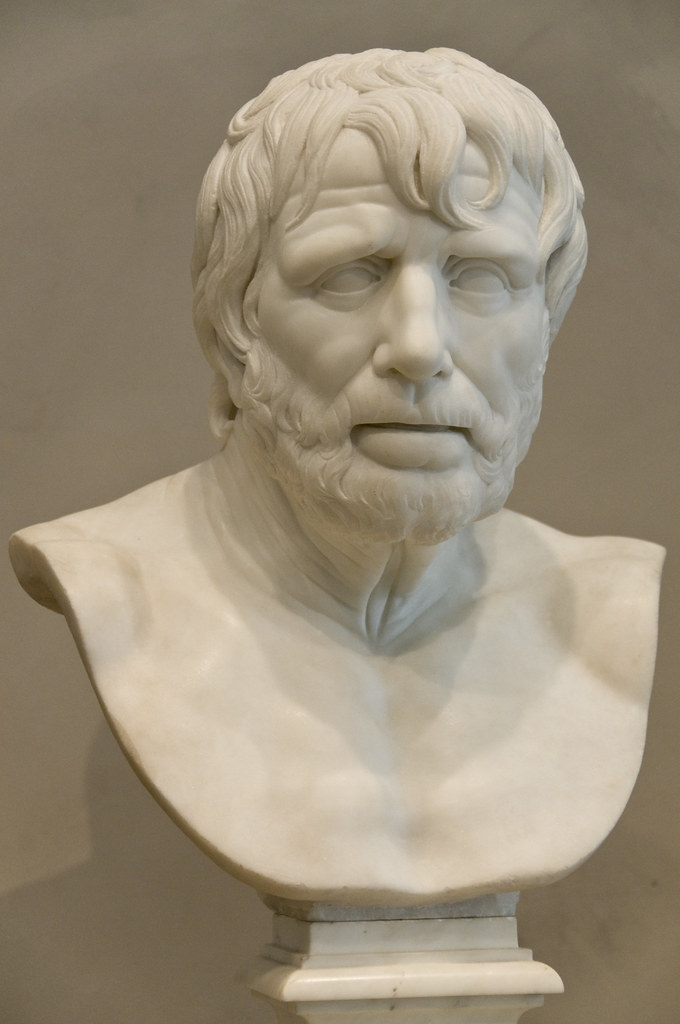

Aeschylus, however, is usually considered the first of the great Greek playwrights, and essentially invented what we think of as drama in the 5th Century BCE (thereby changing Western literature forever) with his introduction of dialogue and interacting characters into play-writing.

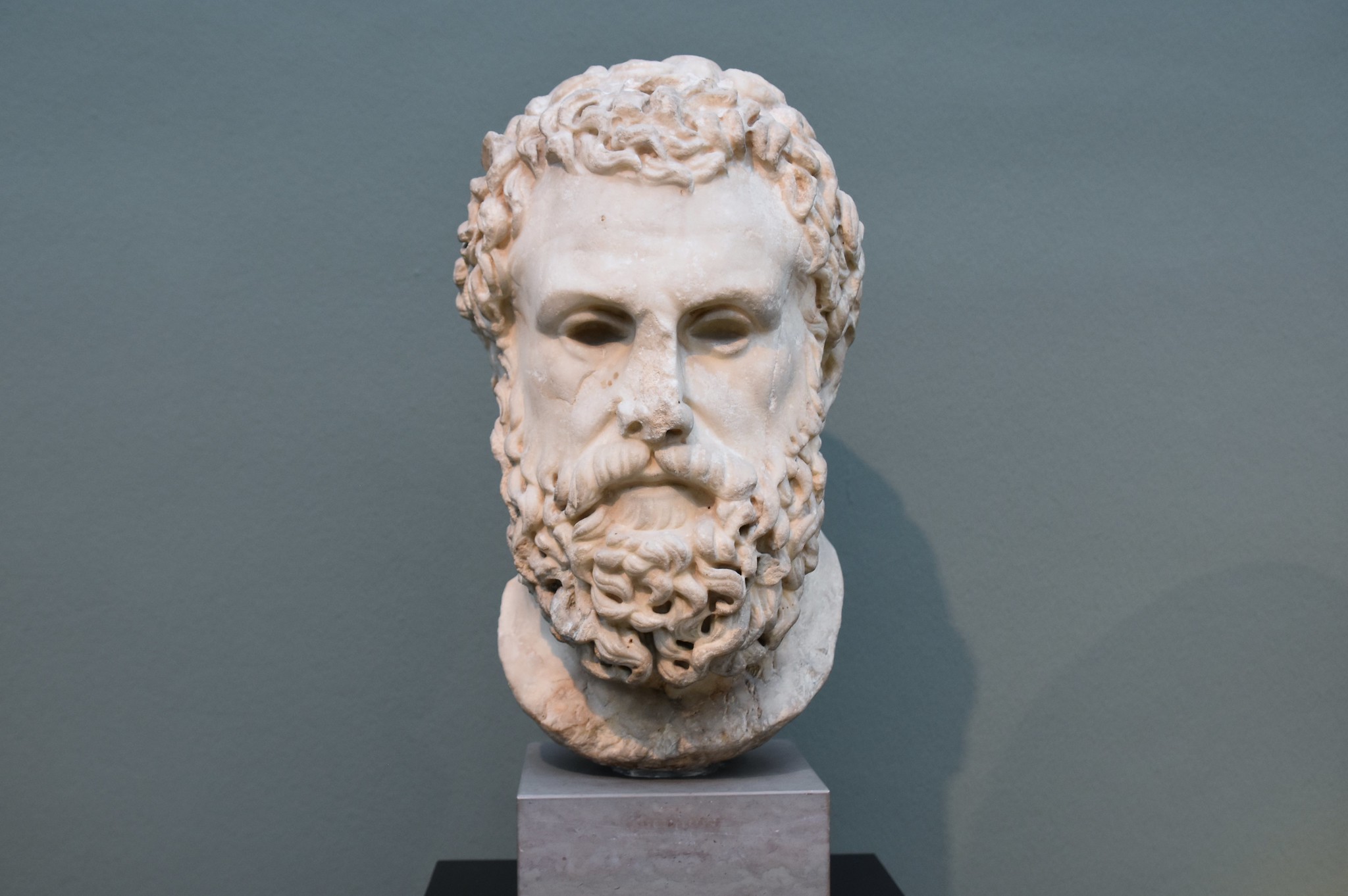

Sophocles is credited with skillfully developing irony as a literary technique, and extended what was considered allowable in drama.

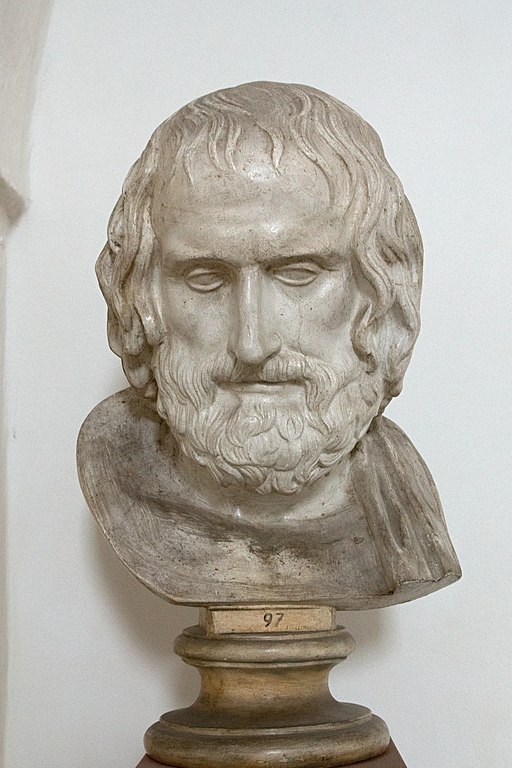

Euripides, on the other hand, used his plays to challenge the societal norms and mores of the period (a hallmark of much of Western literature for the next 2 millennia), introduced even greater flexibility in dramatic structure and was the first playwright to develop female characters to any extent.

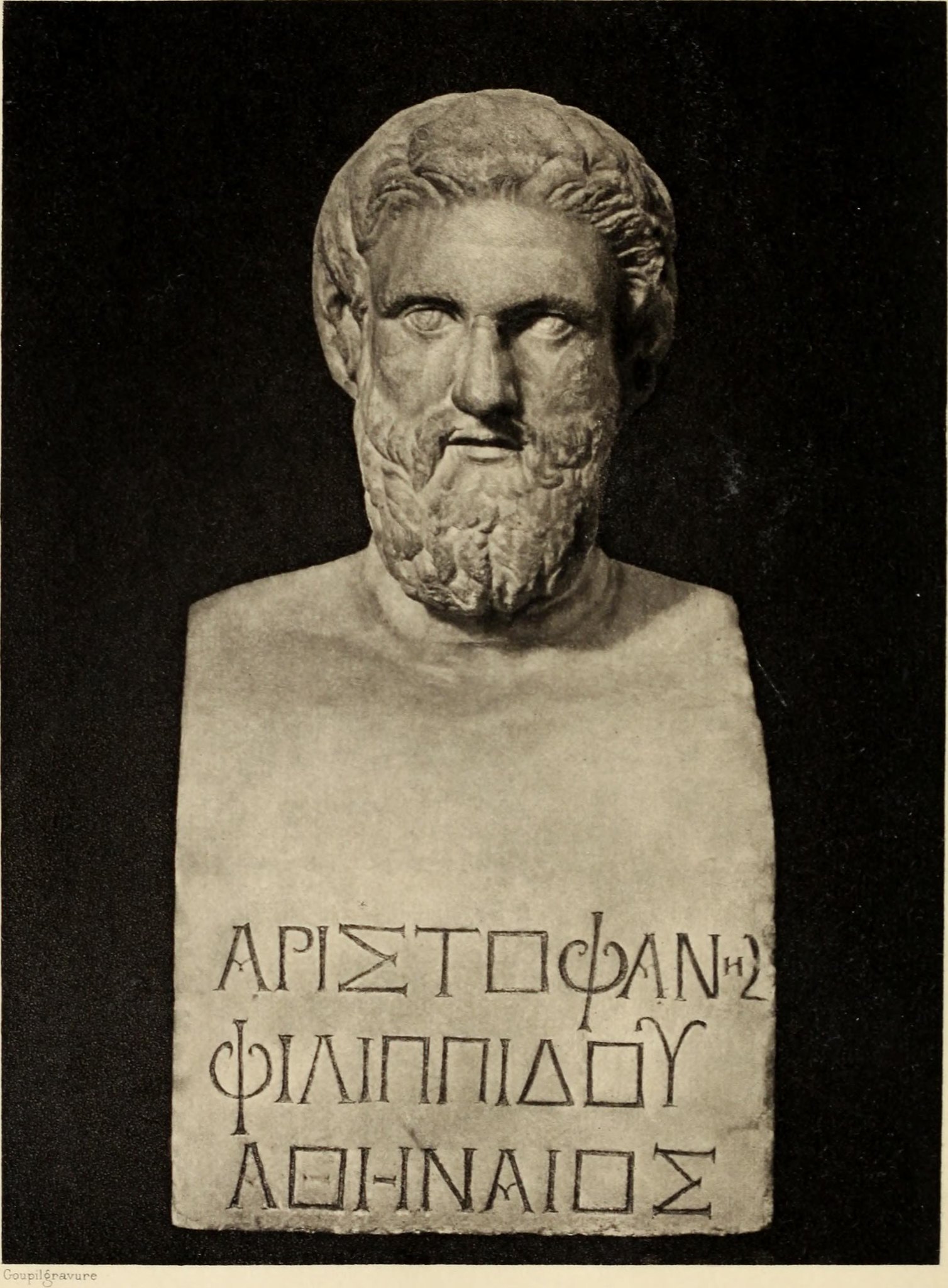

Aristophanes defined and shaped our idea of what is known as Old Comedy, while, almost a century later, Menander carried on the mantle and dominated the genre of Athenian New Comedy.

After Menander, the spirit of dramatic creation moved out to other centres of civilization, such as Alexandria, Sicily and Rome. In the 3rd Century BCE, for example, Apollonius of Rhodes was an innovative and influential Hellenistic Greek epic poet.

After the 3rd Century BCE, Greek literature went into a decline from its previous heights, although much valuable writing in the fields of philosophy, history and science continued to be produced throughout Hellenistic Greece.

Brief mention should also be made here of a lesser known genre, that of the ancient novel or prose fiction. The five surviving Ancient Greek novels, which date to the 2nd and 3rd Century CE are the "Aethiopica" or "Ethiopian Story" by Heliodorus of Emesa, "Chaereas and Callirhoe" by Chariton, "The Ephesian Tale" by Xenophon of Ephesus, "Leucippe and Clitophon" by Achilles Tatius and "Daphnis and Chloe" by Longus.

In addition, a short novel of Greek origin called "Apollonius, King of Tyre", dating to the 3rd Century CEor earlier, has come down to us only in Latin, in which form it became very popular during medieval times.

Main Authors

Greek Verse

Early Greek verse (like Homer's ”Iliad” and ”Odyssey”) was epic in nature, a form of narrative literature recounting the life and works of a heroic or mythological person or group. The traditional metre of epic poetry is the dactylic hexameter, in which each line is made up of six metrical feet, the first five of which can be either a dactyl (one long and two short syllables) or a spondee (two long syllables), with the last foot always a spondee. The formal rhythm is therefore consistent throughout the poem and yet varied from line to line, making it easier to memorize, while preventing it from becoming monotonous (epic poems are often quite long).

Didactic poetry, such as the works of Hesiod, emphasised the instructional and informative qualities in literature, and its primary intention was not necessarily to entertain.

For the ancient Greeks, lyric poetry specifically meant verse that was accompanied by the lyre, usually a short poem expressing personal feelings. These sung verse were divided into stanzas known as strophes (sung by the Chorus as it moved from right to left across the stage), antistrophes (sung by the Chorus in its returning movement from left to right) and epodes (the concluding part sung by the stationary Chorus in centre stage, usually with a different rhyme scheme and structure).

Lyric odes generally dealt with serious subjects, with the strophe and antistrophe looking at the subject from different, often conflicting, perspectives, and the epode moving to a higher level to either view or resolve the underlying issues.

Elegies were a type of lyric poem, usually accompanied by the flute rather than the lyre, of a mournful, melancholic or plaintive nature. Elegiac couplets usually consisted of a line of dactylic hexameter, followed by a line of dactylic pentameter.

Pastorals were lyric poems on rural subjects, usually highly romanticized and unrealistic in nature.

Greek Tragedy

Greek tragedy developed specifically in the Attica region around Athens in the 6th Century or earlier. Classical Greek theatre was written and performed solely by men, including all the female parts and Choruses. The playwrights typically also composed the music, choreographed the dances and directed the actors.

Very early dramas involved just a Chorus (representing a group of characters), and then later a Chorus interacting with a single masked actor, reciting a narrative in verse. The Chorus delivered much of the exposition of the play and expounded poetically on themes.

Aeschylus transformed the art by using two masked actors, as well as the Chorus, each playing different parts throughout the piece, making possible staged drama as we know it. Sophocles introduced three or more actors, allowing still more complexity.

It was a highly stylized (not naturalistic) art form: actors wore masks, and the performances incorporated song and dance. Plays were not generally divided into acts or discrete scenes and, although the action of most Greek tragedies was confined to a twenty-four hour period, time may also pass in non-naturalistic fashion. By convention, distant, violent or complex actions were not directly dramatized, but rather took place offstage, and then were described onstage by a messenger of some sort.

Greek tragedies usually had a consistent structure in which scenes of dialogue ("episodes") alternated with choral songs ("stasimon"), which themselves may or may not be divided into two parts (the "strophe" and the "antistrophe"). Most plays opened with a monologue or "prologue", after which the Chorus usually entered with the first of the choral songs called the "parados". The final scene was called the "exodos".

By the 5th Century, the annual Athens drama festival, known as the Dionysia (in honour of the god of the theatre, Dionysus) had become a spectacular event, lasting four to five days and watched by over 10,000 men. On each of three days, there were presentations of three tragedies and a satyr play (a light comedy on a mythic theme) written by one of three pre-selected tragedians, as well as one comedy by a comedic playwright, at the end of which judges awards first, second and third prizes.

The Lenaia was a similar religious and dramatic annual festival in Athens, although less prestigious and only open to Athenian citizens, and specializing more in comedy.

Greek Comedy

Greek comedy is conventionally divided into three periods or traditions: Old Comedy, Middle Comedy and New Comedy.

Old Comedy is characterized by very topical political satire, tailored specifically to its audience, often lampooning specific public figures using individualized masks and often bawdy irreverence towards both men and gods. It survives today largely in the form of the eleven surviving plays of Aristophanes. The metrical rhythms of Old Comedy are typically iambic, trochaic and anapestic.

Middle Comedy is largely lost (i.e. only relatively short fragments are preserved).

New Comedy relied more on stock characters, rarely attempted to criticize or improve the society it described, and also introduced love interest as a principal element in the drama. It is known today primarily from the substantial papyrus fragments of Menander.

The main elements of a comedy were the parodos (the entrance of the Chorus, chanting or singing verses), one or more parabasis (where the Chorus addresses the audience directly), the agon (a formal debate between the protagonist and antagonist, often with the Chorus acting as judge) and the episodes (informal dialogue between characters, conventionally in iambic trimeter).

Comedies were mainly showcased at the Lenaia festival in Athens, a similar religious and dramatic annual festival to the more prestigious Dionysia, although comedies were also staged at the Dionysia in later years.